Letās say you get an Indication of Interest (IOI) or Letter of Intent (LOI), and the Total Enterprise Value (TEV) offered for your company by an acquirer is $20mm. A quick review of the offer structure will reveal the type of acquirer you are dealing with. Some offers are super clean: Cash-at-Close, with a 5% 12-month escrow, and no financing contingency (e.g. the acquirer doesnāt need to access capital markets after making the offer, which would lock a seller up for 60-90 days in exclusivity if the LOI is signed). These ācleanā offers tend to come from acquirers who are backed by private equity.

But offers may come from an acquirer characterized as a Merchantās Bank (or more broadly a āleveraged buyerā), where the purchase price is paid out over time, after the Cash-at-Close portion is released to you. Beyond Cash-at-Close, these offers may include deal elements that leverage you, like Rolled Shares, Earn-Outs, and Sellerās Notes, along with an escrow (which is a feature of every deal). From an accounting perspective, only a Sellerās Note is considered leverage, strictly speaking. But all of these deal elements beyond Cash-At-Close require you, the seller, to delay payment for, or put at risk, some portion of the purchase price.

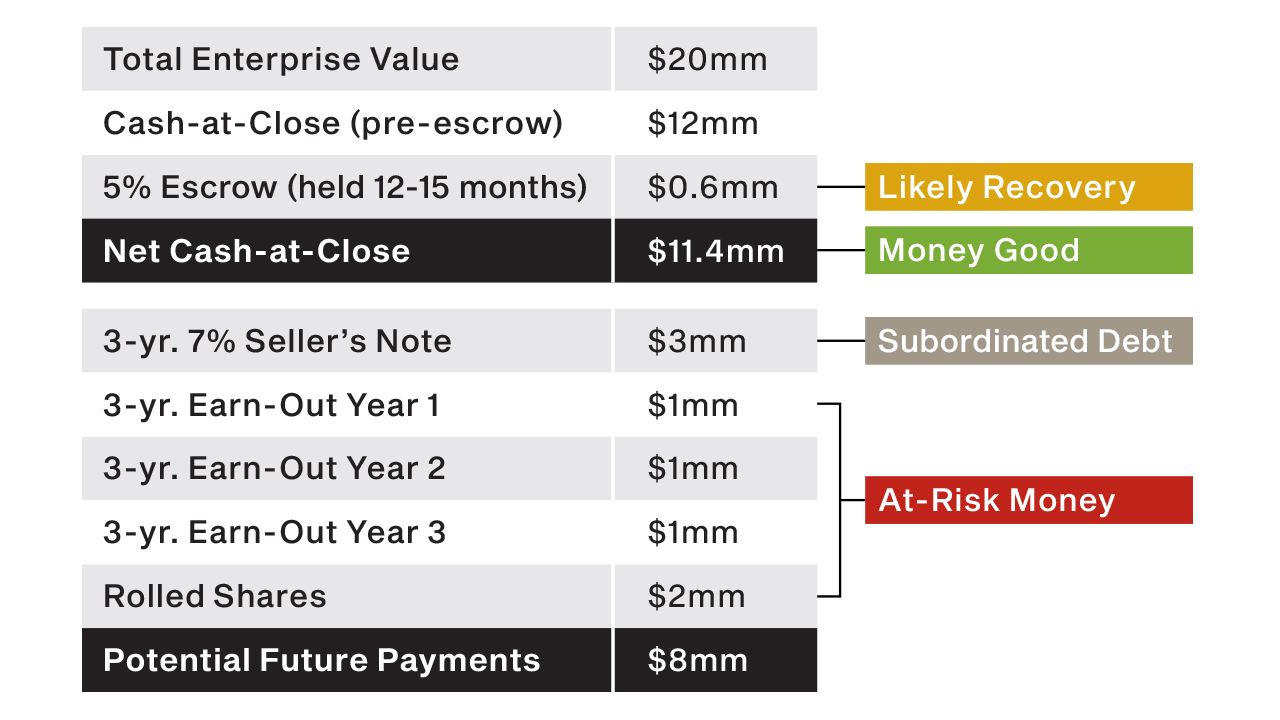

Merchantās Banks make leveraged offers so they risk as little of their own cash as possible orāwith a Sellerās Note āeven borrow some of your money to buy your company. What portion of a Merchantās Bankās offer can be counted as āmoney goodā? Letās break down a $20mm offer with, say, 60% of the dealā$12mmāas Cash-At-Close. First, escrows are unavoidable. Assume 5%. So, reduce that $12mm to $11.4mm, just 57% of the initial total offer. How is the remaining $8mm allocated?

Of the $8mm, assume $3mm is a Sellerās Note. Because itās subordinated debt, acquirers pay 7% to 10% interest (5-year term; interest-only; balloon on the 5th anniversary). Is that money good? Yes, if the acquirer doesnāt bankrupt the āHold-Coā making the acquisition. But it is at risk.

An Earn-Out is often used as a bridging mechanism if the seller and acquirer donāt agree on the purchase price. Letās assume itās $3mm in our sample deal. Easily the least-desirable deal element, Earn-Outs are paid to sellers after you achieve financial objectives by future dates, such as targets in sales, gross profit dollars, or EBITDA. A three-year Earn-Out typically pays $1mm/year. (Some Earn-Outs are tiered; some are all-or-none.) This is highly at-risk money.

With $2mm remaining of the offer, acquirers may ask sellers to invest $2mm into Rolled Shares, an investment in their company (or the NewCo created by the acquisition), so sellers become equity shareholders. Youāll want to examine the financials of the portfolio to ensure itās solid, but even then, acquirers rarely guarantee a future āliquidity event,ā when youād get your $2mm back, ideally with a premium earned. The table below shows how our deal breaks out.

Do leveraged offers ever win deals? Yes. Sometimes leveraged acquirers are the only ones bidding for you, and you really want to sell. Other times, the TEV that is offered is a premium, a figure above the market acquisition value, in open recognition that the acquirer is using multiple funding sources to make the deal happen: 1. Some of their own cash, 2. Bank debt (often 50% or more of the cash-at close portion), 3. A Sellerās Note, 4. Rolled Shares, and 5. Earn-Outs that delay (or maybe reduce or entirely eliminate) the money the acquirer would owe the seller in the years after the closing.

How do you navigate these offers, so you can build in as many layers of protections as possible? Thatās the role your investment banker plays.